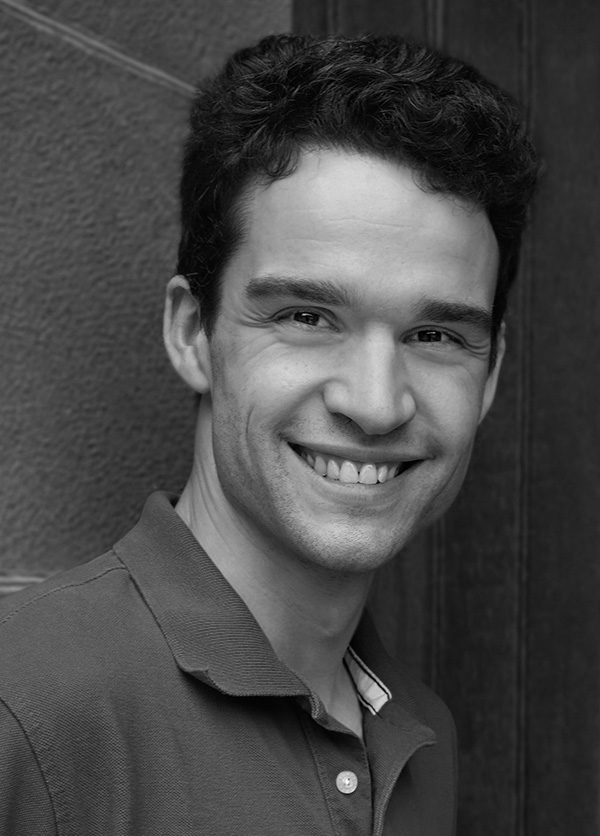

Benjamin Golub

Professor

Department of Economics

and Department of Computer Science (by courtesy)

Northwestern University

Surveys

Eigenvalues in Microeconomics

2025 arXiv

How spectral methods power the microeconomics of networks, from social influence to complex markets.

More

Square matrices often arise in microeconomics, particularly in network models addressing applications from opinion dynamics to platform regulation. Spectral theory provides powerful tools for analyzing their properties. We present an accessible overview of several fundamental applications of spectral methods in microeconomics, focusing especially on the Perron-Frobenius Theorem’s role and its connection to centrality measures. Applications include social learning, network games, public goods provision, and market intervention under uncertainty. The exposition assumes minimal social science background, using spectral theory as a unifying mathematical thread to introduce interested readers to some exciting current topics in microeconomic theory.

Networks and Economic Fragility (with Matt Elliott)

Annual Review of Economics 2022 Publisher's Site

Bad shocks, even fairly small ones, can cause a lot of damage because of network propagation mechanisms. This is a survey of relevant facts and theories, with a focus on extensive margin channels: firms or relationships between them not functioning for a while.

More

Many firms, banks, or other economic agents embedded in a network of codependencies may experience a contemporaneous, sharp drop in functionality or productivity following a shock—even if that shock is localized or moderate in magnitude. We offer an extended review of motivating evidence that such fragility is a live concern in supply networks and in financial systems. Network models of fragility are then reviewed, focusing on the forces that make aggregate functionality especially sensitive to the economic environment. We consider the key structural features of networks that determine their fragility, emphasizing the importance of phase transitions. We then turn to endogenous decisions, both by agents in the models (e.g., firms investing in network formation and robustness) and by planners (e.g., an authority undertaking macroprudential regulation), and discuss some distinctive implications of fragility phenomena for such decisions.

Networks in Economic Development (with Emily Breza, Arun Chandrasekhar, and Aneesha Parvathaneni)

Oxford Review of Exonomic Policy 2019 Publisher's Site

A survey of network models, especially on information diffusion and risk sharing, in the context of economic development.

More

This chapter surveys the implications of studies in network economics for economic development. We focus on information flow and risk-sharing—two topics where work in theory, empirics, and policy analysis have been especially intensive and complementary. In analysing information, we distinguish models of information diffusion and aggregation, and highlight how different models imply very different guidance regarding the right way to seed information. In discussing risk-sharing, we look at the key frictions that impede efficient informal insurance, and some potential unintended consequences when policymakers intervene to help. Throughout, we stress practical insights that can be used with limited measurement of the details of networks.

Learning in Social Networks (with Evan Sadler)

The Oxford Handbook of the Economics of Networks 2016 SSRN Oxford Handbook

A broad overview of two kinds of network learning models: (i) sequential ones in the tradition of information cascades and herding, and (ii) iterated linear updating models (DeGroot), along with their variations, foundations, and critiques. Ideal for a graduate course.

More

This survey covers models of how agents update behaviors and beliefs using information conveyed through social connections. We begin with sequential social learning models, in which each agent makes a decision once and for all after observing a subset of prior decisions; the discussion is organized around the concepts of diffusion and aggregation of information. Next, we present the DeGroot framework of average-based repeated updating, whose long- and medium-run dynamics can be completely characterized in terms of measures of network centrality and segregation. Finally, we turn to various models of repeated updating that feature richer optimizing behavior, and conclude by urging the development of network learning theories that can deal adequately with the observed phenomenon of persistent disagreement. The two parts (sequential and DeGroot) may be read independently, though we take care to relate the different literatures conceptually.

Companion handwritten lecture notes on DeGroot part

Published and forthcoming research papers

When Less is More: Experimental Evidence on Information Delivery During India’s Demonetization (with Abhijit Banerjee, Emily Breza, and Arun Chandrasekhar)

Review of Economic Studies 2024 SSRN NBER Publisher's Site

Suppose people are worried about how asking questions makes them look. Then giving information to fewer people can make for greater diffusion and better learning, in theory and in practice.

More

How should information be disseminated to large populations? The options include broadcasts (e.g., via mass media) and informing a small number of “seeds” who then spread the message. While it may seem natural to try to reach the maximum number of people from the beginning, we show, theoretically and experimentally, that information frictions can reverse this result when incentives to seek are endogenous to the information policy. In a field experiment during the chaotic 2016 Indian demonetization, we varied how information about the policy was delivered to villages along two dimensions: how many people were initially informed (i.e. broadcasting versus seeding) and whether the identities of the initially informed were publicly disclosed (common knowledge). The quality of information aggregation is measured in three ways: the volume of conversations about demonetization, the level of knowledge about demonetization rules, and choice quality in a strongly incentivized decision dependent on understanding the rules. Under common knowledge, broadcasting performs worse and seeding performs better (relative to no common knowledge). Moreover, with common knowledge, seeding is the more effective strategy of the two. These comparisons hold on all three outcomes.

First version: October 20, 2017.

On the Difficulty of Characterizing Network Formation with Endogenous Behavior (with Yu-Chi Hsieh and Evan Sadler)

Mathematical Social Sciences 2024 arXiv Publisher's Site

A recent paper claimed to show that if we combine a coordination game with a network formation game, players naturally sort themselves into cliques with others putting in similar effort levels. But the paper’s analysis is flawed and the result is not correct.

More

Bolletta (Mathematical Social Sciences, 2021) studies a model in which a network is strategically formed and then agents play a linear best-response investment game in it. The model is motivated by an application in which people choose both their study partners and their levels of educational effort. Agents have different one-dimensional types—private returns to effort. A main result claims that (pairwise Nash) stable networks have a locally complete structure consisting of possibly overlapping cliques: if two agents are linked, they are part of a clique composed of all agents with types between theirs. A counterexample shows that the claimed characterization is incorrect. We specify where the analysis errs and discuss implications for network formation models.

Learning from Neighbors about a Changing State (with Krishna Dasaratha and Nir Hak)

Review of Economic Studies 2023 arXiv SSRN Appendix EC 18 conference version Slides Publisher's Site

A model of learning in a network where agents use neighbors’ estimates linearly (as in the famously tractable DeGroot model) but their learning is fully rational and the updating rules are an equilibrium outcome. The rational modeling substantially changes predictions about when a society learns well.

More

Agents learn about a changing state using private signals and their neighbors’ past estimates of the state. We present a model in which Bayesian agents in equilibrium use neighbors’ estimates simply by taking weighted sums with time-invariant weights. The dynamics thus parallel those of the tractable DeGroot model of learning in networks, but arise as an equilibrium outcome rather than a behavioral assumption. We examine whether information aggregation is nearly optimal as neighborhoods grow large. A key condition for this is signal diversity: each individual’s neighbors have private signals that not only contain independent information, but also have sufficiently different distributions. Without signal diversity—e.g., if private signals are i.i.d.—learning is suboptimal in all networks and highly inefficient in some. Turning to social influence, we find it is much more sensitive to one’s signal quality than to one’s number of neighbors, in contrast to standard models with exogenous updating rules.

Final version: December 2022. First version: January 6, 2018.

Exit Spirals in Coupled Networked Markets (with Christoph Aymanns and Co-Pierre Georg)

Operations Research 2023 SSRN Publisher's Site

Strategic agents are involved in two different networks simultaneously. Activity is complementary across networks, and across neighbors. Equilibrium activity in a coupled-network can be very fragile to an aggregate shock, though either network on its own would be robust.

More

Strategic agents choose whether to be active in networked markets. The value of being active depends on the activity choices of specific counterparties. Several markets are coupled when agents’ participation decisions are complements across markets. We model the problem of an analyst assessing the robustness of coupled networked markets during a crisis—an exogenous negative payoff shock—based only on partial information about the network structure. We give conditions under which exit spirals emerge—abrupt collapses of activity following shocks. Market coupling is a pervasive cause of fragility, creating exit spirals even between networks that are individually robust. The robustness of a coupled network system can be improved if one of two markets is replaced by a centralized one, or if links become more correlated across markets.

Current version: January 2023. First version: April 8, 2017.

Supply Network Formation and Fragility (with Matt Elliot and M. V. Leduc)

American Economic Review 2022 arXiv SSRN Appendix Slides Publisher's Site

Firms source inputs through failure-prone relationships with other firms. Equilibrium supply networks are drawn to a precipice: they are very sensitive to small aggregate shocks (e.g., through global shipping congestion or credit shocks).

More

We model the production of complex goods in a large supply network. Each firm sources several essential inputs through relationships with other firms. Individual supply relationships are at risk of idiosyncratic failure, which threatens to disrupt production. To protect against this, firms multisource inputs and strategically invest to make relationships stronger, trading off the cost of investment against the benefits of increased robustness. A supply network is called fragile if aggregate output is very sensitive to small aggregate shocks. We show that supply networks of intermediate productivity are fragile in equilibrium, even though this is always inefficient. The endogenous configuration of supply networks provides a new channel for the powerful amplification of shocks.

First version: September 2019.

Comments and Discussion on “Hidden Exposure: Measuring US Supply Chain Reliance” by Baldwin, Freeman, and Theodorakopoulos (with Yann Calvó-López)

Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 2023 Publisher's Site

Firm-level supply network modeling is crucial for understanding supply chain volatility, even if the focus is macroeconomic. This commentary highlights the limitations of industry-level exposure mapping, introduces the concept of connectivity capital, and analyzes public and private incentive misalignments in sourcing decisions.

More

This comment expands on Baldwin, Freeman, and Theodorakopoulos’ (2024) analysis, emphasizing the importance of firm-level supply network modeling for understanding supply chain volatility — even if the ultimate focus is macroeconomic. We discuss the limitations of their industry-level exposure mapping in capturing crucial microeconomic realities. We review and extend their typology of supply chain shocks, highlighting the understudied role of connectivity capital and connectivity shocks. Drawing on existing literature, we discuss potential misalignments between the incentives of firms and those of a social planner when making sourcing decisions. We use the perspective of supply networks and connectivity shocks to make sense of concerns about indirect exposure to China. We conclude by calling for improved concepts and theories of firm-level sourcing relationships and their disruptions.

Targeting Interventions in Networks (with Andrea Galeotti and Sanjeev Goyal)

Econometrica 2020 Online Appendix Slides Publisher's Site

If a planner has limited resources to shape incentives, whom should she target to maximize welfare? A principal component analysis, new to network games, identifies the planner’s priorities across various network intervention problems.

More

We study games in which a network mediates strategic spillovers and externalities among the players. How does a planner optimally target interventions that change individuals’ private returns to investment? We analyze this question by decomposing any intervention into orthogonal principal components, which are determined by the network and are ordered according to their associated eigenvalues. There is a close connection between the nature of spillovers and the representation of various principal components in the optimal intervention. In games of strategic complements (substitutes), interventions place more weight on the top (bottom) principal components, which reflect more global (local) network structure. For large budgets, optimal interventions are simple–they essentially involve only a single principal component.

First version: October 17, 2017.

A Network Approach to Public Goods (with Matt Elliott)

Journal of Political Economy 2019 4-page version SSRN Online Appendix Slides Publisher's Site

We define a simple index of the (in)efficiency of public goods provision, and show that eigenvector centrality measures play a very natural role in public goods problems. We take a “price theory” approach based on marginal costs and benefits, without parametric assumptions common in the theory of network games.

More

Suppose agents can exert costly effort that creates nonrival, heterogeneous benefits for each other. At each possible outcome, a weighted, directed network describing marginal externalities is defined. We show that Pareto efficient outcomes are those at which the largest eigenvalue of the network is 1. An important set of efficient solutions—Lindahl outcomes—are characterized by contributions being proportional to agents’ eigenvector centralities in the network. The outcomes we focus on are motivated by negotiations. We apply the results to identify who is essential for Pareto improvements, how to efficiently subdivide negotiations, and whom to optimally add to a team.

First version: November 2012.

How Sharing Information Can Garble Experts’ Advice (with Matt Elliott and Andrei Kirilenko)

American Economic Review: Papers & Proceedings 2014 Long Version Publisher's Site

Do we get better advice as our experts get more information? Two experts, who like to be right, make predictions about whether an event will occur based on private signals about its likelihood. It is possible for both experts’ information to improve unambiguously while the usefulness of their advice to any third party unambiguously decreases.

More

We model two experts who must make predictions about whether an event will occur or not. The experts receive private signals about the likelihood of the event occurring, and simultaneously make one of a finite set of possible predictions, corresponding to varying degrees of alarm. The information structure is commonly known among the experts and the recipients of the advice. Each expert’s payoff depends on whether the event occurs and her prediction. Our main result shows that when either or both experts receive uniformly more informative signals, for example by sharing their information, their predictions can become unambiguously less informative. We call such information improvements perverse. Suppose a third party wishes to use the experts’ recommendations to decide whether to take some costly preemptive action to mitigate a possible bad event. Regardless of how this third party trades off the costs of various errors, he will be worse off after a perverse information improvement.

First version: November 21, 2010.

Financial Networks and Contagion (with Matt Elliott and Matthew O. Jackson)

American Economic Review 2014 SSRN Online Appendix Slides Publisher's Site

Diversification (more counterparties) and integration (deeper relationships with each counterparty) have different, non-monotonic effects on financial contagions.

More

We model contagions and cascades of failures among organizations linked through a network of financial interdependencies. We identify how the network propagates discontinuous changes in asset values triggered by failures (e.g., bankruptcies, defaults, and other insolvencies) and use that to study the consequences of integration(each organization becoming more dependent on its counterparties) and diversification (each organization interacting with a larger number of counterparties). Integration and diversification have different, nonmonotonic effects on the extent of cascades. Initial increases in diversification connect the network which permits cascades to propagate further, but eventually, more diversification makes contagion between any pair of organizations less likely as they become less dependent on each other. Integration also faces tradeoffs: increased dependence on other organizations versus less sensitivity to own investments. Finally, we illustrate some aspects of the model with data on European debt cross-holdings.

First version: September 2012.

How Homophily Affects the Speed of Learning and Best-Response Dynamics (with Matthew O. Jackson)

Quarterly Journal of Economics 2012 Online Appendix Slides Publisher's Site

Group-level segregation patterns in networks seriously slow convergence to consensus behavior when agents’ choices are based on an average of neighbors’ choices. When the process is a simple contagion, homophily doesn’t matter.

More

We examine how the speed of learning and best-response processes depends on homophily: the tendency of agents to associate disproportionately with those having similar traits. When agents’ beliefs or behaviors are developed by averaging what they see among their neighbors, then convergence to a consensus is slowed by the presence of homophily, but is not influenced by network density (in contrast to other network processes that depend on shortest paths). In deriving these results, we propose a new, general measure of homophily based on the relative frequencies of interactions among different groups. An application to communication in a society before a vote shows how the time it takes for the vote to correctly aggregate information depends on the homophily and the initial information distribution.

First version: November 24, 2008.

Naive Learning in Social Networks and the Wisdom of Crowds (with Matthew O. Jackson)

American Economic Journal: Microeconomics 2010 3-page version Slides Publisher's Site

In what networks do agents who learn very naively get the right answer?

More

We study learning and influence in a setting where agents receive independent noisy signals about the true value of a variable of interest and then communicate according to an arbitrary social network. The agents naively update their beliefs over time in a decentralized way by repeatedly taking weighted averages of their neighbors’ opinions. We identify conditions determining whether the beliefs of all agents in large societies converge to the true value of the variable, despite their naive updating. We show that such convergence to truth obtains if and only if the influence of the most influential agent in the society is vanishing as the society grows. We identify obstructions which can prevent this, including the existence of prominent groups which receive a disproportionate share of attention. By ruling out such obstructions, we provide structural conditions on the social network that are sufficient for convergence to the truth. Finally, we discuss the speed of convergence and note that whether or not the society converges to truth is unrelated to how quickly a society’s agents reach a consensus.

First version: January 14, 2007.

Using Selection Bias to Explain the Observed Structure of Internet Diffusions (with Matthew O. Jackson)

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2010 PNAS Publisher's Site

David Liben-Nowell and Jon Kleinberg have observed that the reconstructed family trees of chain letter petitions are strangely tall and narrow. We show that this can be explained with selection and observation biases within a simple model.

More

Recently, large data sets stored on the Internet have enabled the analysis of processes, such as large-scale diffusions of information, at new levels of detail. In a recent study, Liben-Nowell and Kleinberg ((2008) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105:4633-4638) observed that the flow of information on the Internet exhibits surprising patterns whereby a chain letter reaches its typical recipient through long paths of hundreds of intermediaries. We show that a basic Galton-Watson epidemic model combined with the selection bias of observing only large diffusions suffices to explain the global patterns in the data. This demonstrates that accounting for selection biases of which data we observe can radically change the estimation of classical diffusion processes.

First version: January 2010.

Does Homophily Predict Consensus Times? Testing a Model of Network Structure via a Dynamic Process (with Matthew O. Jackson)

Review of Network Economics 2012 Publisher's Site

Many random network models forget most of the details of a network, focusing on just a few dimensions of its structure. Can such models nevertheless make good predictions about how a process would run on real networks, in all their complexity?

More

We test theoretical results from Golub and Jackson (2012a), which are based on a random network model, regarding time to convergence of a learning/behavior-updating process. In particular, we see how well those theoretical results match the process when it is simulated on empirically observed high school friendship networks. This tests whether a parsimonious random network model mimics real-world networks with regard to predicting properties of a class of behavioral processes. It also tests whether our theoretical predictions on asymptotically large societies are accurate when applied to populations ranging from thirty to three thousand individuals. We find that the theoretical results account for more than half of the variation in convergence times on the real networks. We conclude that a simple multi-type random network model with types defined by simple observable attributes (age, sex, race) captures aspects of real networks that are relevant for a class of iterated updating processes.

First version: February 2012.

Network Structure and the Speed of Learning: Measuring Homophily Based on its Consequences (with Matthew O. Jackson)

Annals of Economics and Statistics 2012 Publisher's Site

A simple measure of segregation in a network (in which less popular people matter more) predicts quite precisely how long convergence of beliefs will take under a naive process in which agents form their own beliefs by averaging those of their neighbors.

More

Homophily is the tendency of people to associate relatively more with those who are similar to them than with those who are not. In Golub and Jackson (2010a), we introduced degree-weighted homophily (DWH), a new measure of this phenomenon, and showed that it gives a lower bound on the time it takes for a certain natural best-reply or learning process operating in a social network to converge. Here we show that, in important settings, the DWH convergence bound does substantially better than previous bounds based on the Cheeger inequality. We also develop a new complementary upper bound on convergence time, tightening the relationship between DWH and updating processes on networks. In doing so, we suggest that DWH is a natural homophily measure because it tightly tracks a key consequence of homophily — namely, slowdowns in updating processes.

First version: April 2010.

Firms, Queues, and Coffee Breaks: A Flow Model of Corporate Activity with Delays (with R. Preston McAfee)

Review of Economic Design 2011 Publisher's Site

How and when to decentralize networked production — in a model that takes into account ‘human’ features of processing.

More

The multidivisional firm is modeled as a system of interconnected nodes that exchange continuous flows of projects of varying urgency and queue waiting tasks. The main innovation over existing models is that the rate at which waiting projects are taken into processing depends positively on both the availability of resources and the size of the queue, capturing a salient quality of human organizations. A transfer pricing scheme for decentralizing the system is presented, and conditions are given to determine which nodes can be operated autonomously. It is shown that a node can be managed separately from the rest of the system when all of the projects flowing through it are equally urgent.

First version: May 2006.

Stabilizing Brokerage (with Katherine Stovel and Eva Meyersson Milgrom)

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2011 PNAS

Brokers facilitate transactions across gaps in social structure, and there are many reasons for their position to be unstable. Here, we take a look, from a sociological and an economic perspective, at what institutions stabilize brokerage.

More

A variety of social and economic arrangements exist to facilitate the exchange of goods, services, and information over gaps in social structure. Each of these arrangements bears some relationship to the idea of brokerage, but this brokerage is rarely like the pure and formal economic intermediation seen in some modern markets. Indeed, for reasons illuminated by existing sociological and economic models, brokerage is a fragile relationship. In this paper, we review the causes of instability in brokerage and identify three social mechanisms that can stabilize fragile brokerage relationships: social isolation, broker capture, and organizational grafting. Each of these mechanisms rests on the emergence or existence of supporting institutions. We suggest that organizational grafting may be the most stable and effective resolution to the tensions inherent in brokerage, but it is also the most institutionally demanding.

Working Papers

Robust Market Interventions (with Andrea Galeotti, Sanjeev Goyal, Eduard Talamàs and Omer Tamuz)

2025, R&R Journal of Political Economy, extended abstract at EC 2025 arXiv

Tools (“spectral price theory”) for using very noisy measures of demand to design interventions counteracting inefficiencies due to market power

More

When can interventions in markets be designed to increase surplus robustly—i.e., with high probability—accounting for uncertainty due to imprecise information about economic primitives? In a setting with many strategic firms, each possessing some market power, we present conditions for such interventions to exist. The key condition, recoverable structure, requires large-scale complementarities among families of products. The analysis works by decomposing the incidence of interventions in terms of principal components of a Slutsky matrix. Under recoverable structure, a noisy signal of this matrix reveals enough about these principal components to design robust interventions. Our results demonstrate the usefulness of spectral methods for analyzing imperfectly observed strategic interactions with many agents.

Multiplexing in Networks and Diffusion (with Arun G. Chandrasekhar, Vasu Chaudhary, and Matthew O. Jackson)

2024

Different types of social relationships overlap in networks, and we show through data from Indian villages and theory how this multiplexing shapes the spread of information.

More

Social and economic networks are often multiplexed, meaning that people are connected by different types of relationships—such as borrowing goods and giving advice. We make three contributions to the study of multiplexing. First, we document empirical multiplexing patterns in Indian village data: relationships such as socializing, advising, helping, and lending are correlated but distinct, while commonly used proxies like ethnicity and geography are nearly uncorrelated with actual relationships. Second, we examine how these layers and their overlap affect information diffusion in a field experiment. The advice network is the best predictor of diffusion, but combining layers improves predictions further. Villages with greater overlap between layers (more multiplexing) experience less overall diffusion. This leads to our third contribution: we develop a model of diffusion in multiplex networks. Multiplexing slows the spread of simple contagions, such as diseases or basic information, but can either impede or enhance the spread of complex contagions, such as new technologies, depending on their virality. Finally, we identify differences in multiplexing by gender and connectedness. These have implications for inequality in diffusion-mediated outcomes such as access to information and adherence to norms.

Incentive Design with Spillovers (with Krishna Dasaratha and Anant Shah)

2024, extended abstract at EC 2025 arXiv

Optimal incentives for teams under moral hazard: how to structure incentive pay in view of the complementarities in a team.

More

A principal uses payments conditioned on stochastic outcomes of a team project to elicit costly effort from the team members. We develop a multi-agent generalization of a classic first-order approach to contract optimization by leveraging methods from network games. The main results characterize the optimal allocation of incentive pay across agents and outcomes. Incentive optimality requires equalizing, across agents, a product of (i) individual productivity (ii) organizational centrality and (iii) responsiveness to monetary incentives.

Equity Pay in Networked Teams (with Krishna Dasaratha and Anant Shah)

2023, extended abstract at EC 2023 SSRN arXiv

Subsumed by “Incentive Design with Spillovers” — may be of interest for its detailed treatment of a parametric version of that model.

More

Workers contribute effort toward a team output. Each worker’s effort is complementary to the efforts of specific collaborators. A principal motivates workers by paying them shares of the output. We characterize the principal’s optimal allocation of shares. It satisfies a balance condition: for any agent exerting effort, the (complementarity-weighted) sum of shares held by that agent’s collaborators is equal. Moreover, the subset of agents induced to work have tight-knit complementarities: any two members are collaborators or share a common collaborator. We apply our results to study how compensation and output depend on the exogenously given network of complementarities.

Games on Endogenous Networks (with Evan Sadler)

2025, extended abstract at EC 2025 arXiv

People are influenced by the behavior of their peers, but they also choose those peers. We provide a framework, solution concepts, and some applications to show how this changes standard theories of peer effects.

More

We study network games in which players choose the partners with whom they associate as well as an effort level that creates spillovers for those partners. New stability definitions extend standard solution concepts for each choice in isolation: pairwise stability in links and Nash equilibrium in actions. Focusing on environments in which all agents agree on the desirability of potential partners, we identify conditions that determine the shapes of stable networks. The first condition concerns whether higher actions create positive or negative spillovers for neighbors. The second concerns whether actions are strategic complements or substitutes to links. Depending on which combination of these conditions occurs, equilibrium networks are either ordered overlapping cliques or nested split graphs—highly structured forms that facilitate the computation and analysis of outcomes. We apply the framework to examine the consequences of competition for status, to microfound matching models that assume clique formation, and to explain empirical findings in which designing groups to leverage peer effects backfired.

Current version: February 5, 2024. First Version: February 2, 2021

Corporate Culture and Organizational Fragility (with Matt Elliott and M. V. Leduc)

2023, extended abstract at EC 2023 arXiv

A corporate culture that facilitates collaborations in a complex organization is a public good provided in a large group. Nevertheless, it can be voluntarily provided at high levels in equilibrium, though any such equilibrium is necessarily fragile.

More

Complex organizations accomplish tasks through many steps of collaboration among workers. Corporate culture supports collaborations by establishing norms and reducing misunderstandings. Because a strong corporate culture relies on costly, voluntary investments by many workers, we model it as an organizational public good, subject to standard free-riding problems, which become severe in large organizations. Our main finding is that voluntary contributions to culture can nevertheless be sustained, because an organization’s equilibrium productivity is endogenously highly sensitive to individual contributions. However, the completion of complex tasks is then necessarily fragile to small shocks that damage the organization’s culture.

Current version: February 23, 2023. First Version: January 21, 2023.

Discord and Harmony in Networks (with Andrea Galeotti, Sanjeev Goyal and Rithvik Rao )

2021 arXiv

We consider the utilitarian planner’s problem in network coordination games. Welfare is most sensitive to interventions proportional to the last principal component of the network, which relates to local disagreement. Notably, improving welfare worsens other canonical measures of discord.

More

Consider a coordination game played on a network, where agents prefer taking actions closer to those of their neighbors and to their own ideal points in action space. We explore how the welfare outcomes of a coordination game depend on network structure and the distribution of ideal points throughout the network. To this end, we imagine a benevolent or adversarial planner who intervenes, at a cost, to change ideal points in order to maximize or minimize utilitarian welfare subject to a constraint. A complete characterization of optimal interventions is obtained by decomposing interventions into principal components of the network’s adjacency matrix. Welfare is most sensitive to interventions proportional to the last principal component, which focus on local disagreement. A welfare-maximizing planner optimally works to reduce local disagreement, bringing the ideal points of neighbors closer together, whereas a malevolent adversary optimally drives neighbors’ ideal points apart to decrease welfare. Such welfare-maximizing/minimizing interventions are very different from ones that would be done to change some traditional measures of discord, such as the cross-sectional variation of equilibrium actions. In fact, an adversary sowing disagreement to maximize her impact on welfare will minimize her impact on global variation in equilibrium actions, underscoring a tension between improving welfare and increasing global cohesion of equilibrium behavior.

Current version: February 26, 2021

Signaling, Shame, and Silence in Social Learning (with Arun Chandrasekhar and He Yang)

2019 SSRN NBER

Does the fear of appearing ignorant deter people from asking questions, and is that an important friction in information-gathering? In an experiment, we show that people seek information less when needing it is related to ability.

More

We examine how a social stigma of seeking information can inhibit learning. Consider a Seeker of uncertain ability who can learn about a task from an Advisor. If higher-ability Seekers need information less, then a Seeker concerned about reputation may refrain from asking to avoid signaling low ability. Separately, low-ability individuals may feel inhibited even if their ability is known and there is nothing to signal, an effect we term shame. Signaling and shame constitute an overall stigma of seeking information. We distinguish the constituent parts of stigma in a simple model and then perform an experiment with treatments designed to detect both effects. Seekers have three days to retrieve information from paired Advisors in a field setting. The first arm varies whether needing information is correlated with a measure of cognitive ability; the second varies whether a Seeker’s ability is revealed to the paired Advisor, irrespective of the seeking decision. We find that low-ability individuals do face large stigma inhibitions: there is a 55% decline in the probability of seeking when the need for information is correlated with ability. The second arm allows us to assess the contributions of signaling and shame, and, under structural assumptions, to estimate their relative magnitudes. We find signaling to be the dominant force overall. The shame effect is particularly pronounced among socially close pairs (in terms of network distance and caste co-membership) whereas signaling concerns dominate for more distant pairs.

Current version: May 2019. First version: December 11, 2016.

Expectations, Networks, and Conventions (with Stephen Morris)

2017 SSRN Slides

We study certain games in which there is both incomplete information and a network structure. The two turn out to be, in a sense, the same thing: A unified analysis nests classical incomplete-information results (e.g., on common priors) and network results (e.g. relating equilibria to network centralities).

More

In coordination games and speculative over-the-counter financial markets, solutions depend on higher-order average expectations: agents’ expectations about what counterparties, on average, expect their counterparties to think, etc. We offer a unified analysis of these objects and their limits, for general information structures, priors, and networks of counterparty relationships. Our key device is an interaction structure combining the network and agents’ beliefs, which we analyze using Markov methods. This device allows us to nest classical beauty contests and network games within one model and unify their results. Two applications illustrate the techniques: The first characterizes when slight optimism about counterparties’ average expectations leads to contagion of optimism and extreme asset prices. The second describes the tyranny of the least-informed: agents coordinating on the prior expectations of the one with the worst private information, despite all having nearly common certainty, based on precise private signals, of the ex post optimal action.

Current version: September 10, 2017. First version: April 24, 2017.

Higher-Order Expectations (with Stephen Morris)

2017 SSRN

Motivated by their role in games, we study limits of iterated expectations with heterogeneous priors: how priors matter, how the order in which expectations are taken matters, and when the two enter “separably”.

More

We study higher-order expectations paralleling the Harsanyi (1968) approach to higher-order beliefs—taking a basic set of random variables as given, and building up higher-order expectations from them. We report three main results. First, we generalize Samet’s (1998a) characterization of the common prior assumption in terms of higher-order expectations, resolving an apparent paradox raised by his result. Second, we characterize when the limits of higher-order expectations can be expressed in terms of agents’ heterogeneous priors, generalizing Samet’s expression of limit higher-order expectations via the common prior. Third, we study higher-order average expectations—objects that arise in network games. We characterize when and how the network structure and agents’ beliefs enter in a separable way.

Current version: August 31, 2017. First version: June 1, 2017.

Older Working Papers

The Leverage of Weak Ties: How Linking Groups Affects Inequality (with Carlos Lever)

2010

Arbitrarily weak bridges linking social groups can have arbitrarily large consequences for inequality.

More

Centrality measures based on eigenvectors are important in models of how networks affect investment decisions, the transmission of information, and the provision of local public goods. We fully characterize how the centrality of each member of a society changes when initially disconnected groups begin interacting with each other via a new bridging link. Arbitrarily weak intergroup connections can have arbitrarily large effects on the distribution of centrality. For instance, if a high-centrality member of one group begins interacting symmetrically with a low-centrality member of another, the latter group has the larger centrality in the combined network — in inverse proportion to the centrality of its emissary! We also find that agents who form the intergroup link, the “bridge agents”, become relatively more central within their own groups, while other intragroup centrality ratios remain unchanged.

Current version: April 12, 2010.

Strategic Random Networks and Tipping Points in Network Formation (with Yair Livne)

2011

If agents form networks in an environment of uncertainty, then arbitrarily small changes in economic parameters (such as costs and benefits of linking) can discontinuously change the properties of the equilibrium networks, especially efficiency.

More

Agents invest costly effort to socialize. Their effort levels determine the probabilities of relationships, which are valuable for their direct benefits and also because they lead to other relationships in a later stage of “meeting friends of friends”. In contrast to many network formation models, there is fundamental uncertainty at the time of investment regarding which friendships will form. The equilibrium outcomes are random graphs, and we characterize how their density, connectedness, and other properties depend on the economic fundamentals. When the value of friends of friends is low, there are both sparse and thick equilibrium networks. But as soon as this value crosses a key threshold, the sparse equilibria disappear completely and only densely connected networks are possible. This transition mitigates an extreme inefficiency.

Current version: November 2, 2010. First version: April, 2010.

Ranking Agendas for Negotiations (with Matt Elliott)

2015

Countries are hashing out the agenda for a summit in which each will make costly concessions to help the others. Should the summit focus on pollution, trade tariffs, or disarmament? This is a theory to help them decide based on marginal costs and benefits, without transferable utility.

More

Consider a negotiation in which agents will make costly concessions to benefit others—e.g., by implementing tariff reductions, environmental regulations or disarmament policies. An agenda specifies which issue or dimension each agent will make concessions on; after an agenda is chosen, the negotiation comes down to the magnitude of each agent’s contribution. We seek a ranking of agendas based on the marginal costs and benefits generated at the status quo, which are captured in a Jacobian matrix for each agenda. In a transferable utility (TU) setting, there is a simple ranking based on the best available social return per unit of cost (measured in the numeraire). Without transfers, the problem of ranking agendas is more difficult, and we take an axiomatic approach. First, we require the ranking not to depend on economically irrelevant changes of units. Second, we require that the ranking be consistent with the TU ranking on problems that are equivalent to TU problems in a suitable sense. The unique ranking satisfying these axioms is represented by the spectral radius (Frobenius root) of a matrix closely related to the Jacobian, whose entries measure the marginal benefits per unit marginal cost agents can confer on one another.

First version: May 1, 2014. Current version: February 22, 2015.